Coming Into Place -Lamoine, Douglas County

By Lauren Paige Loebsack

A child born to a farming family is born into a world deeply connected with the seasons. We are children growing up whose home lives ebb and flow with the changing demands of weather and growth cycles. We are immersed in a world of observation and consideration of the sky. We can recite the years of hard winters, drought and bounty. I have watched again and again my world awaken in the spring, the bare earth revealed as the snow melts away, the shy green hue of the fragile first shoots of wheat turn into seas of green that fade to gold. Then shorn, naked, exposed and patient for its winter rest and the cycle to unfold again, each one its own chapter in the story of this place.

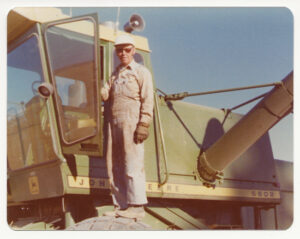

The farm is place and family. The pictures on our walls capture the changes in both as they grow together with the larger world. Children grow taller, mature, grandparents disappear. Behind them, the backdrop of the farm does the same. In one of oldest pictorial records of my family homestead, the new, simple square house sits singularly against the rolling hills of wheat, my great-grandfather, with his father and others, stands beside a mule drawn wagon topped with sacks of wheat, all cast in sepia tones. Later, the picture now in color, my grandfather operates an open cab combine, his face lost behind a kerchief and sunglasses to protect from the dust and chaff.

The farm is place and family. The pictures on our walls capture the changes in both as they grow together with the larger world. Children grow taller, mature, grandparents disappear. Behind them, the backdrop of the farm does the same. In one of oldest pictorial records of my family homestead, the new, simple square house sits singularly against the rolling hills of wheat, my great-grandfather, with his father and others, stands beside a mule drawn wagon topped with sacks of wheat, all cast in sepia tones. Later, the picture now in color, my grandfather operates an open cab combine, his face lost behind a kerchief and sunglasses to protect from the dust and chaff.

The house in the background has grown too, a large addition, an out building, the trees planted a generation before now tall and filled in. Later, the combines have closed cabs and each sports a painted number, “1” through “4”. Grandpa Lawrence was “Unit 1”, my great uncle Leland “Unit 2”, my father “Unit 3” and my cousin David “Unit 4”. My father still uses “Unit 3” as his radio handle, though we have had only one combine for nearly two decades. A recent picture, now on social media, features the smiling face of my baby sister as she drives the combine, my niece sitting beside her. They wave from the comfort of a sleek, air-conditioned cab atop a massive green machine.

My great, great grandparents came out West with so many others during the Homestead Act, pausing in North Dakota long enough to catch their breath and scratch up some food. The farm they would come to tend looked much like the idyllic image many Americans probably have of the family farm. Children worked as they could, the youngest on simple tasks like gathering the eggs from the hen house, the older children taking on new tasks as their strength and dexterity allowed. Farmers pushed their wide brimmed hats up over their weathered face to cool their brow for a moment, with work shirts tucked into slacks held up over wiry frames by suspenders. The women wore skirts and gathered beans from the garden in their aprons.

My great, great grandparents came out West with so many others during the Homestead Act, pausing in North Dakota long enough to catch their breath and scratch up some food. The farm they would come to tend looked much like the idyllic image many Americans probably have of the family farm. Children worked as they could, the youngest on simple tasks like gathering the eggs from the hen house, the older children taking on new tasks as their strength and dexterity allowed. Farmers pushed their wide brimmed hats up over their weathered face to cool their brow for a moment, with work shirts tucked into slacks held up over wiry frames by suspenders. The women wore skirts and gathered beans from the garden in their aprons.

Quietly, less visibly, but like the equipment and the people, the ways we farm have changed. Once the farm was Life, cut out from the earth. We farmed to survive, to grow the food that literally sustained the family. The farm then became a career, albeit a unique one, and industrialization changed the game to one of economic prosperity. One could, if hard working and lucky enough, make a living, go on vacation, retire.

Now farms face a new world, one of sustainability. From the soil, what many would call dirt, farmers coax out a plant that becomes food for many. The machines and chemicals now available can outpace Mother Nature’s ability to respond. This soil can be worked to death. It takes a millennium for the sun and rain to weather rock into a skiff of top soil and all can be swept away by a single wind storm or rain event. The farmer will watch with dread as the needed rain falls too hard, too fast and scours deep cuts into the carefully tended field. Farmers now employ “no-till” farming methods, along with many other efforts that include GPS driven machinery and thorough meteorological research to protect our most precious partner: the land.

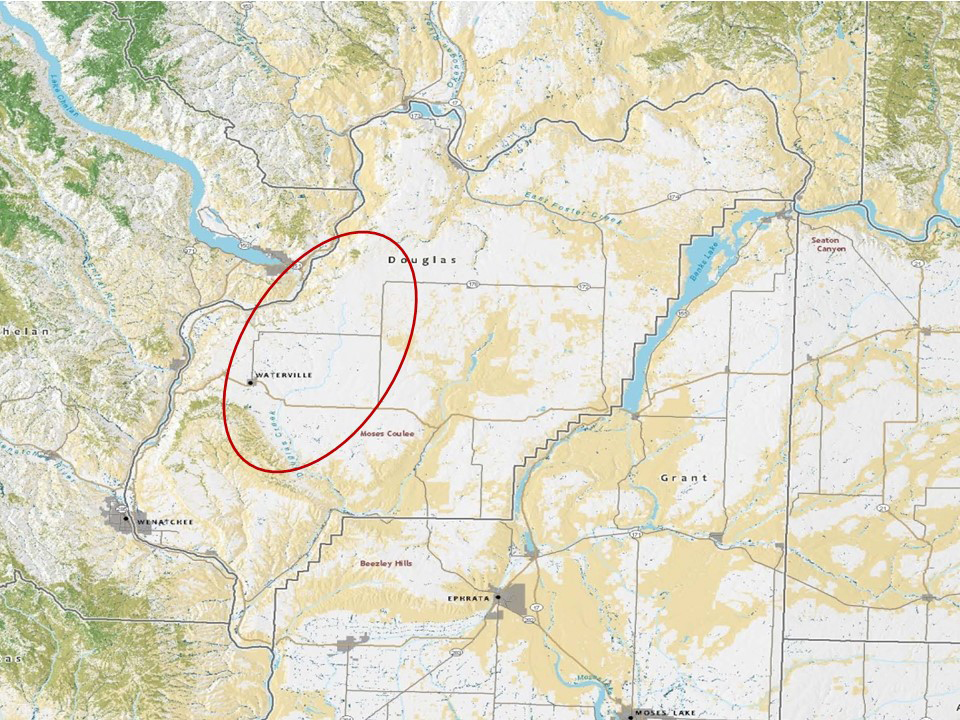

I grew up in a little community once called Arup, but that I have always known as Lamoine. The legend, if you can call such a story “legend”, goes that Arupp was founded ahead of the railroad, hoping to be that special place the trains would pass through. When the post office was being secured, a new name was chosen by a Mr. Leonard Nathan Bragg who ran the general store at the time, naming it Lamoine after a brand of sardines he carried on his shelves. Why the name was changed from Arupp is lost to time. The house I called home, that I still think of as “home”, sits cozied up to Road G. Just a few hundred feet to the east, in a field, still stands the remains of the old Lamoine school house. We spent a lot of time there as children, chasing pigeons around the rafters and playing all manner of pretend, until the little building was deemed unsafe by our mothers. The farmer who owns the land still plows around the little building, respectful, giving it enough room to stand against time. A sign was installed beside it, on the north side so as to be visible from the highway. The sign reads “Lamoine School 1915-1924”.

In the wide-open spread of the Waterville plateau, we keep our landmarks for practical and personal purposes. They dot the land, mileposts of the history of settlement and the changing interpretation of the American dream. This practice of letting time, not man, determine the lifespan of these landmarks illuminates a deep truth: that the land, this place, is an enduring member of the family, growing with us all, shaped by deliberate action and natural courses, the matriarch that binds together the rest of the family. She both rules and serves us, watches us grow and leave and return, embraces our husbands and wives and children, all with an innate wisdom to be what each generation needs.

Now, as a woman no longer bound to the cycles of the farm, sometimes what I need is just to visit, to feel the comfort of that enduring presence and the memories it has held for generations. Like my father, I like to set out on a drive to “check on the wheat”, to see a particular hill and think of the times we’ve been there before and be inspired by the endurance of the earth and those who have worked it. To remember that I sprouted from here, will become a seed that is dropped to awaken as the roots of the next crop, in the same earth as my fore fathers.

October 30, 2021 @ 3:23 pm

We used the own some land at the top of McNeil Canyon and I would intentionally drive through Waterville to get there and always looked forward to seeing Lamoine on the way. I have taken photos of the schoolhouse as well as other crumbling home and windmills across Douglas County. We finally sold the land as the smoke from the fires every year were too much for my asthma. I always felt very peaceful and rather at home there even though we live in western Washington. My wife grew up in Brewster and that is why we were motivated to buy a place there. I have always dreamed of living in a small farm house there and working a large garden to help at the table. But alas, at 75 I am probably too old to pull up roots and go. I love the story and photos. Makes me wistful. Thank you for posting this.

October 30, 2021 @ 9:31 pm

Thank you for sharing your memories about that part of the region. I’ll pass this on to Lauren.

Nancy Warner