Thinking like a Community

Connecting Our Stories to Shape Our Future

Appreciating this region and the place we call home is a process and an adventure that fills lifetimes and spans generations. Learning the lay of the land and developing a sense of the seasons, social and professional networks, and needs of the region takes time – knowing what to expect and who to go to for help to move our ideas forward are markers of a place we think of as home. It’s where success starts – where our stories of a sustainable future begin.

So, it stands to reason that we can better understand each other and collaborate more easily if we know each other’s stories about how we came to make our home here whether it was recently, or generations ago.

In that spirit IRIS is inviting residents across the region to share their Coming into Place stories that explore our respective attachments to this region. Please enjoy the stories that follow and consider submitting your own.

Coming Into Place, Orondo, Douglas County

Coming Into Place, Orondo, Douglas County

By Jessi Mendoza

My parents immigrated to North Central Washington from the state of Michoacan, Mexico in the 1970’s when they were both teenagers. Growing up in the small village Coahuayana, near the Pacific Ocean, they wanted to live in a small town so they followed family members who were already living in Central Washington. They both have siblings who spoke highly about the beauty and abundance of the area. Jobs, housing, and excellent weather were among the things that attracted them to come here.

My Father

My dad originally moved to Yakima, where he had many family members who were working in the agricultural industry. He heard rumors of the Wenatchee Valley and the many opportunities for work with excellent wages. Along with my uncle, they decided to take the risk and make the move to the valley.

The first stop was Entiat. They didn’t have much luck finding work at first since there were already many workers moving into the area. They kept hearing about these well-paying jobs available with free housing so their search continued. They headed north and stopped at Lake Chelan, where my Uncle Salomon found a job. But since they only had room for one new employee, my dad and a friend continued the search and found jobs in the beautiful Twin W Orchard on the Columbia near Orondo that included livable wages and housing. They worked hard and felt like they could build a life in this new country. Their hard work paid off as they both received work residency permits in order to work peacefully.

The first stop was Entiat. They didn’t have much luck finding work at first since there were already many workers moving into the area. They kept hearing about these well-paying jobs available with free housing so their search continued. They headed north and stopped at Lake Chelan, where my Uncle Salomon found a job. But since they only had room for one new employee, my dad and a friend continued the search and found jobs in the beautiful Twin W Orchard on the Columbia near Orondo that included livable wages and housing. They worked hard and felt like they could build a life in this new country. Their hard work paid off as they both received work residency permits in order to work peacefully.

My Mother

My mother was curious to see what it was like to live and work in the USA. So, as a 15-year-old teenager she decided to move to Orondo, in 1975. She received help from my aunt who was working in Lake Chelan at a fruit packing shed. Unfortunately, she came during the winter which was a shock to her as she was used to palm trees, sunny weather, and being able to walk outside whenever she wanted.

Staying at home all day while my aunt and uncle worked was not only lonely, but she felt like a prisoner, locked inside without being able to comfortably go outside. She immediately wrote a letter pleading to my grandmother to send money in order to send her back to Mexico. My aunt explained the benefits of the spring and summertime and convinced my mom to not send the letter. Her decision to stay paid off because she met my father later that year. My mother Eva and my father Jesus met in the Twin W Orchards in Orondo when they were coincidently matched up as picking partners.

lonely, but she felt like a prisoner, locked inside without being able to comfortably go outside. She immediately wrote a letter pleading to my grandmother to send money in order to send her back to Mexico. My aunt explained the benefits of the spring and summertime and convinced my mom to not send the letter. Her decision to stay paid off because she met my father later that year. My mother Eva and my father Jesus met in the Twin W Orchards in Orondo when they were coincidently matched up as picking partners.

My mom’s dad was a cattle farmer, butcher, grocery store owner, and corn farmer in the mountains of Santa Maria, Michoacan. My mother and her seven siblings helped my grandparents in various ways with the farm and the store. Both my mom and dad had to leave school by the third grade to financially support their families. Back in Mexico my dad did manual labor cleaning up yards and providing landscaping services, while my mom helped customers in my grandparent’s grocery store.

My mom eventually started her own daycare business out of our home in Orondo shortly after having my younger brother German in 1991. She was tired of working in the orchard and also working in the fruit shed in Chelan. She became an entrepreneur just like my grandparents.

My Childhood

As a young Hispanic kid growing up around apple and pear orchards in Orondo, it was like having the largest playground I could ever ask for. With views of the mighty Columbia River, I knew I was living in a special place. I enjoyed walking down to the river and fishing on the river banks. My family and I lived in housing provided by the orchard owners in the middle of Twin W Ranch. The orchard had mostly apple trees including red delicious, gala, and golden delicious. There were a few acres with Bartlett pears as well.

As a young Hispanic kid growing up around apple and pear orchards in Orondo, it was like having the largest playground I could ever ask for. With views of the mighty Columbia River, I knew I was living in a special place. I enjoyed walking down to the river and fishing on the river banks. My family and I lived in housing provided by the orchard owners in the middle of Twin W Ranch. The orchard had mostly apple trees including red delicious, gala, and golden delicious. There were a few acres with Bartlett pears as well.

There were only a couple dozen families living in Twin W, but lucky for me I had many cousins who living there and were close to my age. My cousins and I would play games in the middle of the orchards and go on adventures to distant areas. Growing up with family members and having many large gatherings made this place feel like home.

The Orondo School- A Gathering Place

I enjoyed going to school in Orondo because of the great teachers who made learning fun. I was able to relate to many of my Hispanic classmates in school but it was tough sometimes at first connecting with others because I only knew Spanish. After learning English in preschool and kindergarten I was able to make other friends who were not Hispanic. The teachers and community were and still are very welcoming to the Hispanic culture and people. We would all have fun at the Orondo scholarship fundraisers, Bingo Night being the most popular. Everyone got along and was there for a great cause. It felt great to belong to such a generous and kind community. And although both of my parents didn’t know English they still participated and donated when they could.

The Orondo School was a great gathering place for many community members to go in and obtain any type of help they may need. My parents and countless other family members took advantage of English classes hosted at the school. This was a tremendous benefit as they were able to better communicate with upper management, excel at their jobs, and be promoted.

I reflect and how much fun I had at the Orondo School and am very happy when I am able to help out during the Bingo Night Fundraiser. I see so many familiar faces and I remember why this place feels like home. Occasionally I will run into other Orondo alums who look familiar and get this instinctual reaction that they are from my home. They grew up in Orondo.

I reflect and how much fun I had at the Orondo School and am very happy when I am able to help out during the Bingo Night Fundraiser. I see so many familiar faces and I remember why this place feels like home. Occasionally I will run into other Orondo alums who look familiar and get this instinctual reaction that they are from my home. They grew up in Orondo.

It’s great to see these people around in the community. I enjoy going back to Orondo and seeing folks come together regardless of differences in cultures and race. Most community members work in the agriculture industry and they are able connect, relate, and bond because of that.

Working hard

My parents remain humble and grateful to this day and they instilled that in me and all my siblings. My parents brought with them a strong work ethic, a desire to learn, and a dream to create a better life for themselves and their family. They built just that and have given my siblings and I the best opportunity we could ever have hoped for. This is the best country we could be in to make our dreams come true. My mom and dad sacrificed so many things in order for my siblings and I to pursue an education. All my siblings and I have a college education because of what they instilled in us.

in me and all my siblings. My parents brought with them a strong work ethic, a desire to learn, and a dream to create a better life for themselves and their family. They built just that and have given my siblings and I the best opportunity we could ever have hoped for. This is the best country we could be in to make our dreams come true. My mom and dad sacrificed so many things in order for my siblings and I to pursue an education. All my siblings and I have a college education because of what they instilled in us.

My parents left their home country and everything that they have ever known, coming to the U.S. unable to speak English, in order to pursue something better. That was going far beyond their comfort zone, an example that has taught me to push myself harder in order to make my own dreams come true which I believe sets me up for success. I will follow the example they have provided by always working hard, remaining persistent, having a vision for what I want then going after it and making it happen!

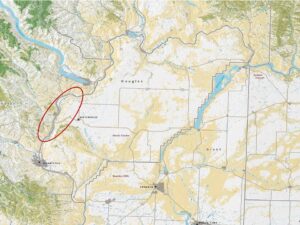

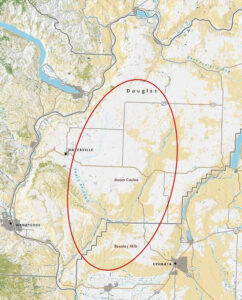

Coming Into Place, Moses Coulee-Beezley Hills

Coming Into Place, Moses Coulee-Beezley Hills, Douglas and Grant counties

By Nancy Warner

Most of us who live in North Central Washington came from someplace else. Except for tribal members whose roots go back hundreds and hundreds of years, the rest of us either came from families who immigrated from other states and countries or we came here on our own, sometimes at the urging of friends.

Collectively, when we immigrated here – from as far away as Germany or as close as Seattle – we brought values, traditions, knowledge, and skills that have helped shape this place. That’s something we all have in common. As immigrants, we’ve also all experienced the need to find help along the way – help in getting oriented to a new landscape and community, help starting a new job and making new friends – help making this place feel like home, a place where we belong.

For me, it was the chance to contribute to the conservation of the wide-open sagebrush country – or shrub-steppe – that prompted my family to move here from Colorado in 2000. My husband Chuck and I had been working as program managers for The Nature Conservancy since the 1980s, an international non-profit organization dedicated to conserving plants, animals and natural systems. We enjoyed the challenge of trying to balance conservation with farming, ranching, and the maintenance of strong, rural communities. We liked the process of really getting to know a place and the people and working with them to find ways to make nature and people thrive.

So we were excited to have the chance to start a new program for the Conservancy that would focus on working with other private and public landowners in the Moses Coulee-Beezley Hills area of Douglas and Grant counties. We were fired up about conserving the shrub lands, wildflowers, and wildlife that together represent the most ecologically diverse and threatened habitat type in Washington. To succeed we would have to understand the needs of the plants and animals – from pygmy rabbits to Indian tobacco – as well as those of neighboring farmers, ranchers, and public land managing agencies. We needed to be able to think like a whole community, human and non-human alike.

But other things were new to us particularly basalt, the dark molten rock that dominates and defines the shrub steppe in the Columbia Basin. The significantly shorter winter and longer summer days of the Northwest also claimed our attention at first. And while I’ve always loved apples, we had never lived in a place where there were so many orchards – apricots, cherries, peaches, pears, and apples – presenting wave after wave of blooms through the spring. We had also known some pretty big rivers in other parts of the West, but nothing like the Columbia and the hydroelectric dams that still and channel its flow.

While we had a great circle of researchers and land managers to work with, many of them having had years of experience in this landscape, it quickly became clear that we needed more information about past human use of the Moses Coulee-Beezley Hills area to effectively think like a community and consider the roles of grazing, hunting, farming, traditional gathering, and wetland and upland restoration in the management of the Conservancy’s lands. As it turned out, many of our neighbors and longtime residents were willing to help us fill in some of those information gaps by allowing us to record their stories.

This practice of gathering oral histories, ground-tested knowledge earned by the people who had lived in a place for a long time, was one of the interests and skills I brought with me to this region. I’d reached out to local residents for help in better understanding a landscape before, gathering oral histories in other places we’d lived including Cache Valley in Utah, the Carrizo Plain in California and the San Luis Valley in Colorado. In all of these places I’d found people anxious to help me get my bearings in a new home – to help me understand how a given landscape or community works by sharing their memories and insights – their experiences, what they’ve seen and learned over the years, and what they appreciate about their place.

Recognizing the value of these stories and the process of gathering them, I began to work with a new organization, the Initiative for Rural Innovation & Stewardship (IRIS) to expand this practice starting in 2005. Since then, I’ve been working with IRIS and many partners to gather, share, and care for nearly 600 stories about successes in this region in formats that range from audio recordings and videos to photo collections and printed publications. See www.ncwcollections.org

Those of us with IRIS believe that the process of gathering and sharing success stories enhances a sense of belonging, inspires action and builds community – all conditions that lead to success. Together this collection of stories helps us learn more about the nature of this place – the natural landscape and the human community, informs actions about what works, and highlights core values that continue to shape the way we live in this place. We hope you enjoy sampling these stories. We invite you to share them with others and to add your own story of success that can help others come into this place.

Coming Into Place -Lamoine, Douglas County

By Lauren Paige Loebsack

A child born to a farming family is born into a world deeply connected with the seasons. We are children growing up whose home lives ebb and flow with the changing demands of weather and growth cycles. We are immersed in a world of observation and consideration of the sky. We can recite the years of hard winters, drought and bounty. I have watched again and again my world awaken in the spring, the bare earth revealed as the snow melts away, the shy green hue of the fragile first shoots of wheat turn into seas of green that fade to gold. Then shorn, naked, exposed and patient for its winter rest and the cycle to unfold again, each one its own chapter in the story of this place.

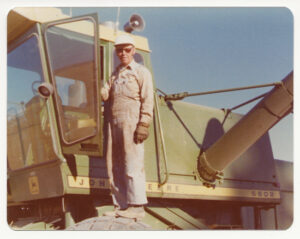

The house in the background has grown too, a large addition, an out building, the trees planted a generation before now tall and filled in. Later, the combines have closed cabs and each sports a painted number, “1” through “4”. Grandpa Lawrence was “Unit 1”, my great uncle Leland “Unit 2”, my father “Unit 3” and my cousin David “Unit 4”. My father still uses “Unit 3” as his radio handle, though we have had only one combine for nearly two decades. A recent picture, now on social media, features the smiling face of my baby sister as she drives the combine, my niece sitting beside her. They wave from the comfort of a sleek, air-conditioned cab atop a massive green machine.

Quietly, less visibly, but like the equipment and the people, the ways we farm have changed. Once the farm was Life, cut out from the earth. We farmed to survive, to grow the food that literally sustained the family. The farm then became a career, albeit a unique one, and industrialization changed the game to one of economic prosperity. One could, if hard working and lucky enough, make a living, go on vacation, retire.

Now farms face a new world, one of sustainability. From the soil, what many would call dirt, farmers coax out a plant that becomes food for many. The machines and chemicals now available can outpace Mother Nature’s ability to respond. This soil can be worked to death. It takes a millennium for the sun and rain to weather rock into a skiff of top soil and all can be swept away by a single wind storm or rain event. The farmer will watch with dread as the needed rain falls too hard, too fast and scours deep cuts into the carefully tended field. Farmers now employ “no-till” farming methods, along with many other efforts that include GPS driven machinery and thorough meteorological research to protect our most precious partner: the land.

I grew up in a little community once called Arup, but that I have always known as Lamoine. The legend, if you can call such a story “legend”, goes that Arupp was founded ahead of the railroad, hoping to be that special place the trains would pass through. When the post office was being secured, a new name was chosen by a Mr. Leonard Nathan Bragg who ran the general store at the time, naming it Lamoine after a brand of sardines he carried on his shelves. Why the name was changed from Arupp is lost to time. The house I called home, that I still think of as “home”, sits cozied up to Road G. Just a few hundred feet to the east, in a field, still stands the remains of the old Lamoine school house. We spent a lot of time there as children, chasing pigeons around the rafters and playing all manner of pretend, until the little building was deemed unsafe by our mothers. The farmer who owns the land still plows around the little building, respectful, giving it enough room to stand against time. A sign was installed beside it, on the north side so as to be visible from the highway. The sign reads “Lamoine School 1915-1924”.

In the wide-open spread of the Waterville plateau, we keep our landmarks for practical and personal purposes. They dot the land, mileposts of the history of settlement and the changing interpretation of the American dream. This practice of letting time, not man, determine the lifespan of these landmarks illuminates a deep truth: that the land, this place, is an enduring member of the family, growing with us all, shaped by deliberate action and natural courses, the matriarch that binds together the rest of the family. She both rules and serves us, watches us grow and leave and return, embraces our husbands and wives and children, all with an innate wisdom to be what each generation needs.

Now, as a woman no longer bound to the cycles of the farm, sometimes what I need is just to visit, to feel the comfort of that enduring presence and the memories it has held for generations. Like my father, I like to set out on a drive to “check on the wheat”, to see a particular hill and think of the times we’ve been there before and be inspired by the endurance of the earth and those who have worked it. To remember that I sprouted from here, will become a seed that is dropped to awaken as the roots of the next crop, in the same earth as my fore fathers.

Coming Into Place

Introduction

By Nancy Warner

Initiative for Rural Innovation & Stewardship

Most of us who make our home here in North Central Washington came from someplace else. Regardless of when and how we arrived, most of us were drawn here by an enticing mix of opportunities, hopes, and dreams. And when we came, we also brought values, traditions, knowledge, and skills with us – characteristics that have helped shape this region.

That’s something we all have in common. We all have a story – stories that when shared can grow understanding not just about each other but also about our communities.

Gathering those stories and sharing them in ways that can help people connect around success in the region has been the work of IRIS for the past 15 years. One of the more than 300 recorded stories IRIS has collected and archived with the North Central Washington Library is that of David Weber – a descendant of pioneer farmers whose story is one example of why Quincy sees itself as a place of “Opportunities Unlimited.”

Weber Ridge Farms in Grant County

David Weber – Harvest Time, 2017

“It’s a desert, pure and simple”, wrote Lieutenant Thomas Symons in the 1870’s after making a several year study of the Columbia Basin for the Army Corps of Engineers. It’s always been one of my favorite quotes, as it shows the difficulty of not only living here, but of making a living in agriculture as well. It makes you wonder, why would anyone choose to live in the Quincy Valley? Well, I choose to live here, and am still farming some of the same ground as my grandparents who chose to come here 115 years ago, despite the words of Thomas Symons.

My grandparents probably didn’t know any better. They were German Russians immigrants, who staked everything to come to America in 1902. With deteriorating conditions for German speaking people in Russia, they knew it was time to “get out”. One brother in the family, whom we call Uncle Adam, came first to America in the late 1800’s, thinking to follow many other Germans and settle in Nebraska or the Dakotas. But while on the train, he met a man, probably a developer or promoter of some sort, who told him he really needed to go to Walla Walla, Washington, as the whole region had Homestead Act land for the taking, the last of it in the United States. This meant an opportunity to acquire their own farm land much faster than in other areas. Uncle Adam followed this advice, possibly even taking a loan from the man. After being in Walla Walla for a while, this industrious and entrepreneurial man found land to buy in the Odessa and Ritzville areas, then Quincy. Other family began immigrating, and my grandparents and two small children came over through Ellis Island in 1902, taking the train west to Odessa and arriving in Quincy via horse and wagon.

What they must have thought when they arrived here, a place of only around 8 inches of precipitation a year, after leaving the beautiful Russian steppes of the Volga. There is a family story of how my grandmother cried into the pancake batter nearly every morning with the dust swirling around their first home, a tent. She had left her mother and father behind, never to see them again! They certainly didn’t gain an easier life by coming here, but the main difference was in the freedom to choose their own path. They embraced the hardships with a strong faith in God, a knowledge of farming, hard work ethic, extended family that all worked together and an ability to find fulfillment in the simple things of life. They never expected to become wealthy, but rather to work in harmony with the earth to sustain their family, as generations before them had done.

I now reap the benefits of that legacy and of the difficult decision to leave everything they knew behind, and start anew. From them, I carry the pioneer spirit on. This is the place I call home.

David Weber – Harvest Time, 2017